Fundamentals of Economics

I. Introduction

The term economics derives from the Greek words οἰκονομία from οἶκος (oikos, "house") and νόμος (nomos, "custom" or "law") and so translates as “law or rules of the house(hold). In earlier

centuries called ‘Political Economy’ economists in the late 19th century suggested the differentiation from political and other social sciences and therefore the term economics

established itself. To many Economics may appear to be the study of complicated charts, tables, statistics and numbers, but actually economics is the study of human behaviour, specifically in the

fulfilment of people's unlimited needs and wants in relation to their limited resources.

For example, most individuals face the problem of having only limited resources to fulfil their wants and needs and therefore must make certain choices how to spend their money.

People spend part of their money on monthly bills like rent and electricity, furthermore for food and clothes to fulfil basic needs. Then usually people spend the rest to fulfil their wants, go

for a drink, watch a movie in the cinema or to go on holidays. Economics study the choices made and look deeper into why for example money was spend for holidays instead of getting a new fridge.

Economists may want to know if people would still go for a pint of Guinness if the price increased by £2. The fundamental character of economic science is the attempt of understanding how nations

and individuals respond to specific constraints.

Therefore economics is clearly a social science studying certain aspects of society. The assumption is made that human beings will aim to fulfil their self-interests. Economists also assume that people are rational in their efforts to fulfil their unlimited wants and needs.

Adam Smith, by many called the "father of modern economics" and author of the, first published in 1776, famous book "An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations", brought it all down to the question why some nations and countries prospered while others live in poorness and destitution. In the centuries after him economists also looked into the question how resources of a nation are allocated and how this may affect their wealth.

In the early 20th

century Alfred Marshall, author of "The Principles Of Economics", reflects on economics: "Thus it is on one side the study of wealth; and on the other, and more important side, a part of the study of

man." (Marshall, 1920, p.

28).

II. Economics - What is it ?

In order to begin one first needs to understand (1) the concept

of scarcity and (2) the two branches of study within economics: microeconomics and macroeconomics.

Scarcity

One of the basic economic problems is scarcity, which arises because people have infinite wants but only finite resources. That creates tension between our limited resources and our unlimited wants and needs. For an individual, resources include time, money and skill. For a country, limited resources include natural resources, capital, labour force and technology.

Because all of our resources are limited in comparison to all of our wants and needs, individuals and nations have to make decisions regarding what goods and services they can buy and which ones they must forgo. Individuals, firms, countries need to allocate their resources efficiently. For example, if you choose to buy one DVD as opposed to two video tapes, you must give up owning a second movie of inferior technology in exchange for the higher quality of the one DVD. Of course, each individual and nation will have different values, but by having different levels of (scarce) resources, people and nations each form some of these values as a result of the particular scarcities with which they are faced.

So, because of scarcity, people and economies must make decisions over how to allocate their resources. These decisions are made by giving up (trading off) one want to satisfy

another which economics calls the opportunity cost. Economics, in turn, aims to study why we make these decisions and how we allocate our resources most efficiently.

Macro- and Microeconomics

Macro and microeconomics are the two vantage points from which the economy is observed. Macroeconomics looks at the total output of a nation and the way the nation allocates its limited resources of land, labour and capital in an attempt to maximize production levels and promote trade and growth for future generations. After observing the society as a whole, Adam Smith noted that there was an "invisible hand" turning the wheels of the economy: a market force that keeps the economy functioning.

Microeconomics looks into similar issues, but on the level of the individual people and firms within the economy. It tends to be more scientific in its approach, and studies the parts that make up the whole economy. Analysing certain aspects of human behaviour, microeconomics shows us how individuals and firms respond to changes in price and why they demand what they do at particular price levels.

Micro and macroeconomics are intertwined; as economists gain understanding of certain phenomena, they can help nations and individuals make more informed decisions when allocating

resources. The systems by which nations allocate their resources can be placed on a spectrum where the command economy is on the one end and the market economy is on the other. The market economy

advocates forces within a competitive market, which constitute the "invisible hand", to determine how resources should be allocated. The command economic system relies on the government to decide

how the country's resources would best be allocated. In both systems, however, scarcity and unlimited wants force governments and individuals to decide how best to manage resources and allocate

them in the most efficient way possible. Nevertheless, there are always limits to what the economy and government can do.

III. Production Possibility Frontier, Growth, Opportunity Cost and Trade

Production Possibility Frontier

Under the field of macroeconomics, the production possibility frontier (PPF) represents the point at which an economy is most efficiently

producing its goods and services and, therefore, allocating its resources in the best way possible. If the economy is not producing the quantities indicated by the PPF, resources are being

managed inefficiently and the production of society will dwindle. The production possibility frontier shows there are limits to production, so an economy, to achieve efficiency, must decide what

combination of goods and services can be produced.

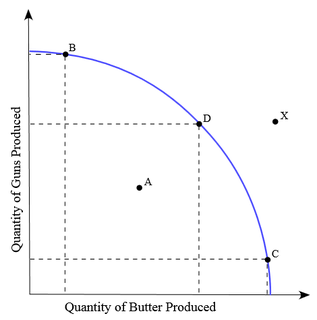

Let's turn to the chart. Imagine an economy that can produce only butter and guns. According to the PPF, points B, C and D - all appearing on the curve - represent the most efficient use of resources by the economy. Point A represents an inefficient use of resources, while point X represents the goals that the economy cannot attain with its present levels of resources.

It appears in order for this economy to produce more butter, it must give up some of the

resources it uses to produce guns (point C). If the economy starts producing more guns (represented by points D and B), it would have to divert resources from making butter and

will consequently produce less butter than it is producing at point C. As the chart shows, by moving production from point C to D, the economy must decrease butter production by a

certain amount. However, if the economy moves from point D to B, butter output will be significantly reduced while the increase in guns will be high. Keep in mind that B, D and C all

represent the most efficient allocation of resources for the economy; the nation must decide how to achieve the PPF and which combination to use. If more butter is in demand, the cost of

increasing its output is proportional to the cost of decreasing gun production.

Point A means that the country's resources are not being used efficiently or, more specifically, that the country is not producing enough butter or guns given the potential of its resources. Point X, as we mentioned above, represents an output level that is currently unreachable by this economy. However, if there was a change in technology while the level of land, labour and capital remained the same, the time required to produce butter and guns would be reduced. Output would increase, and the PPF would be pushed outwards. A new curve, on which X would appear, would represent the new efficient allocation of resources.

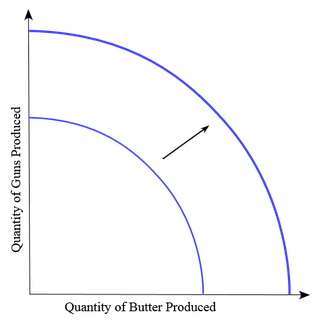

When the PPF shifts outwards, we know there is growth in an economy. Alternatively, when the PPF shifts inwards it indicates that the economy is shrinking as a result of a decline in its most efficient allocation of resources and optimal production capability. A shrinking economy could be a result of a decrease in supplies or a deficiency in technology.

An economy can be producing on the PPF curve only in theory. In

reality, economies constantly struggle to reach an optimal production capacity. And because scarcity forces an economy to forgo one choice for another, the slope of the PPF will always be

negative; if production of product A increases then production of product B will have to decrease accordingly.

Opportunity Cost

Opportunity cost is the value of what is foregone in order to have something else. This value is unique for each individual. You may, for instance, forgo ice cream in order to have an extra helping of mashed potatoes. For you, the mashed potatoes have a greater value than dessert. But you can always change your mind in the future because there may be some instances when the mashed potatoes are just not as attractive as the ice cream. The opportunity cost of an individual's decisions, therefore, is determined by his or her needs, wants, time and resources (income).

1. The cost of an alternative that must be forgone in order to pursue a certain action. Put another way, the benefits you could have received by taking an alternative action.

2. The difference in return between a chosen investment and one that is necessarily passed up. Say you invest in a stock and it returns a paltry 2% over the year. In placing your money in the stock, you gave up the opportunity of another investment - say, a risk-free government bond yielding 6%. In this situation, your opportunity costs are 4% (6% - 2%).

This is important to the PPF because a country will decide how to best allocate its resources according to its opportunity cost. Therefore, the previous wine/cotton example shows that if the country chooses to produce more wine than cotton, the opportunity cost is equivalent to the cost of giving up the required cotton production.

Let's look at another example to demonstrate how opportunity cost ensures that an individual will buy the least expensive of two similar goods when given the choice. For example, assume that an individual has a choice between two telephone services. If he or she were to buy the most expensive service, that individual may have to reduce the number of times he or she goes to the movies each month. Giving up these opportunities to go to the movies may be a cost that is too high for this person, leading him or her to choose the less expensive service.

Remember that opportunity cost is different for each individual

and nation. Thus, what is valued more than something else will vary among people and countries when decisions are made about how to allocate resources.

Trade, Comparative Advantage and Absolute Advantage

Specialization and Comparative Advantage

An economy can focus on producing all of the goods and services it needs to function, but this may lead to an inefficient allocation of resources and hinder future growth. By using specialization, a country can concentrate on the production of one thing that it can do best, rather than dividing up its resources.

For example, let's look at a hypothetical world that has only two

countries (Country A and Country B) and two products (butter and guns). Each country can make guns and/or butter. Now suppose that Country A has very little fertile land and an abundance of

steel for gun production. Country B, on the other hand, has an abundance of fertile land but very little steel. If Country A were to try to produce both guns and butter, it would need to

divide up its resources. Because it requires a lot of effort to produce butter by irrigating the land, Country A would have to sacrifice producing guns. The opportunity cost of producing both

cars and cotton is high for Country A, which will have to give up a lot of capital in order to produce both. Similarly, for Country B, the opportunity cost of producing both products is high

because the effort required to produce guns is greater than that of producing butter.

Each country can produce one of the products more efficiently (at a lower cost) than the other. Country A, which has an abundance of steel, would need to give up more guns than Country B would to produce the same amount of butter. Country B would need to give up more butter than Country A to produce the same amount of guns. Therefore, County A has a comparative advantage over Country B in the production of guns, and Country B has a comparative advantage over Country A in the production of butter.

Now let's say that both countries (A and B) specialize in producing the goods with which they have a comparative advantage. If they trade the goods that they produce for other goods in which they don't have a comparative advantage, both countries will be able to enjoy both products at a lower opportunity cost. Furthermore, each country will be exchanging the best product it can make for another good or service that is the best that the other country can produce. Specialization and trade also works when several different countries are involved. For example, if Country C specializes in the production of corn, it can trade its corn for guns from Country A and butter from Country B.

Determining how countries exchange goods produced by a comparative advantage ("the best for the best") is the backbone of international trade theory. This method of exchange is considered an optimal allocation of resources, whereby economies, in theory, will no longer be lacking anything that they need. Like opportunity cost, specialization and comparative advantage also apply to the way in which individuals interact within an economy.

Absolute Advantage

Sometimes a country or an individual can produce more than

another country, even though countries both have the same amount of inputs. For example, Country A may have a technological advantage that, with the same amount of inputs (arable land, steel,

labor), enables the country to manufacture more of both guns and butter than Country B. A country that can produce more of both goods is said to have an absolute advantage. Better quality

resources can give a country an absolute advantage as can a higher level of education and overall technological advancement. It is not possible, however, for a country to have a comparative

advantage in everything that it produces, so it will always be able to benefit from trade.