Leadership and Leading Change

John P. Kotter

“Leading

Change: Why transformation Efforts Fail”

Is any

specific leadership style the right one to succeed in leading change?

A. Introduction

Studies from management consulting agencies like Arthur D. Little or McKinsey & Co. show that about two-thirds of transformational efforts of companies fail despite the substantial resources committed to their change programs. After studying the success and failure in change initiatives John Kotter came up with an eight step model to transform an organisation. He argues that “the most general lesson to be learned from the more successful cases is that the change process goes through a series of phases that, in total, usually require a considerable length of time” and “that critical mistakes in any of the phases can have a devastating impact, slowing momentum and negating hard-won gains” (1995, pp. 59-60). Although some of Kotter’s ideas may appear obvious they should not be underestimated during a transformation process. First, Kotter emphasizes on establishing a sense of urgency, to continue with the motivational drivers and the creation and communication of the vision while empowering others to act on this vision. The planning and creation of short-term wins and the formalization of new processes and procedures are accounted by him as motivational factors along the way to his final step of institutionalising new approaches.

Following a review of John Kotter’s article “Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail” the reader may rise the question if there is any one specific leading style which is the right one to succeed in leading change. Therefore it will be examined what leadership actually is and several leading styles will be described to discuss them in combination with established models of leading change.

In the final part the author will describe Michael Dell’s leadership style and his

ability to lead change while transforming DELL Inc. back to where they once were, one of the leading tech companies of the world.

B. Leadership and Leading Change

To evaluate Kotter’s concept of eight steps to transforming an organisation, different leadership styles need to be examined and essential questions to be answered to determine if any leadership style would empower a leader to specifically lead change.

-

What makes a leader a leader?

-

Is there such thing as a born leader?

-

If leaders are not born as such, do they actively become leaders or are they made leaders?

1. Leadership Styles

From Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King, to Caesar and Napoleon, there may be as many styles to lead as there are leaders.

1.1. Naturalistic Leadership Theories

Among the early theories about leadership is the idea that leaders are born as such and not made leaders. The assumption was that leadership qualities are inherent and probably hereditary. Later from these naturalistic approaches the trait theories, still assuming leaders are born as such, rose. In contrast to behavioural theories trait theories do not look at a leader’s behaviour but argue that effective leaders share a number of common personality characteristics, or ‘traits’ that naturally qualifies them as leaders. Kirkpatrick and Locke (1991, p. 48)argue that “key leader traits include: drive […]; leadership motivation […]; honesty and integrity; self-confidence […]; cognitive ability; and knowledge of the business”. Though obvious these traits and characteristics pose a major role in good leadership Ralph Stogdill (1948, p. 64)concluded in 1948 that “A person does not become a leader by virtue of the possession of some combination of traits” because his research showed that there are no universally existing traits identical in business, political and military leaders.

1.2. Lewin’s Leaderships Styles

In 1939 the German Psychologist Kurt Lewin (Lewin, et al., 1939) argued that leadership works best in a participative environment. He identified three main leadership styles:

-

Autocratic - The leader informs what must be done. Most or all decisions are made by the leader without involvement of employees.

-

Democratic - Some decision-making powers are given to employees while the final decision is still made by the leader.

-

Laissez-faire or delegative - This being a rather relaxed leadership style, almost all decision-making-control is given to staff. While granting independence this may only work on employees that are also responsible for maintaining control of their work and at a particular skill-level, where they do not need a push from superiors.

1.3. Theory X and Theory Y

In 1960 Douglas McGregor (1960) contrasted on two theories on human motivation and management; he called these Theory X and Theory Y.

While theory X assumes that employees generally have no ambition or incentive to work because they dislike working and avoid responsibility, employees need to be forced and threatened to deliver what is needed, directed, controlled and supervised at every step. Theory Y on the other hand describes a de-centralized, participative style of management assuming employees are generally creative and happy to work and in fact seek responsibility as a self-motivation to enjoy working.

McGregor noticed that X-Type workers usually are the minority but for example in

large scale production environments, X Theory management may be unavoidable.

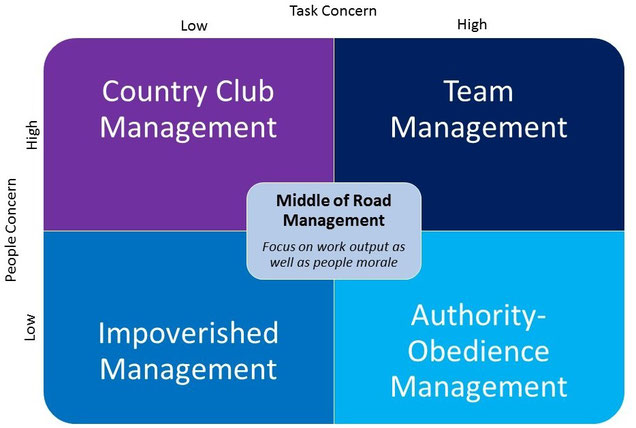

1.4. The Blake-Mouton Leadership Grid

According to Blake and Mouton (Team FME, 2015, pp. 10-13) and their leadership model from 1964, the best style to lead is the ‘Team-Management-Style – High-Production/High-People’. Understanding the organization's purpose and the employee’s commitment to the organization’s success leads to high satisfaction and motivation and therefore to high results.

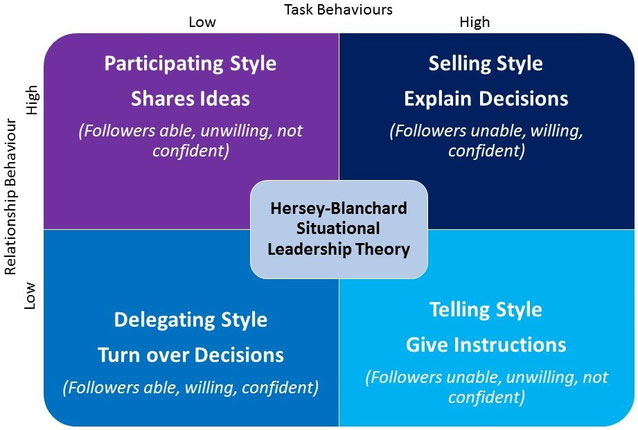

1.5. The Hersey-Blanchard Situational Leadership Theory

The Hersey-Blanchard Situational Leadership Theory (Team FME, 2015, p. 25), first published in 1969, elaborates that,

depending on the maturity of the team members, different styles need to be used. Arguing that a more directing approach should be used while working with immature employees and with a growing

maturity of the people a more participative, delegating style is adequate. As there are no teams and team members that are created equal they argue that leaders are more effective when their

leadership is based on the groups or individuals they are leading.

1.6. Transformational and Transactional Leadership

In 1978 James McGregor Burns (1978) established the ideas of transformational and transactional leadership. The transformational model was further developed by Bernard Bass in 1985. The four components are sometimes referred to as the four I’s:

-

Idealized Influence – Leading by example; while the leader is considered as a role model, he therefor is admired

-

Inspirational Motivation – Leading by inspiring and motivating employees

-

Individualized Consideration – Leading by demonstrating genuine concern for the individual needs of employees.

-

Intellectual Stimulation – Leading by requiring innovation and creativeness

Combining the first two constitutes the leader’s individual ‘charisma’. Although transformational leaders are often wrongly considered as being ‘soft’ they actually constantly challenge their employees to thrive for higher performance.

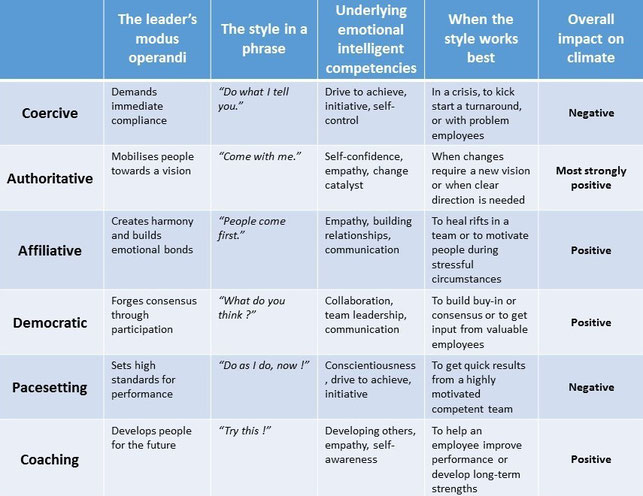

1.7. Goleman’s Six Emotional Leadership Styles

In their book ‘Primal Leadership’ Goleman, Boyatzis and McKee (2001) described six distinct emotional leadership styles. While two of their styles – ‘Coercive’ and ‘Pacesetting’ – can create tension and therefore should only be used carefully in specific situations, the other four styles – ‘Authoritative’, ‘Coaching’, ‘Affiliative’ and ‘Democratic’ – have the positive outcome of promoting harmony.

According to Goleman (2000) the six styles should be used interchangeably, adapting to the specific

situation and the needs of the people that have to be handled.

2. Leading Change

However, no business can survive over the long-term without the ability to re-invent itself. Heraclitus already expressed the thought that change is the only constant in life more than 2500 years ago saying “You could not step twice into the same river”. Therefore the ultimate test for leaders regardless of their leading style may be the ability of guiding or leading ‘change’.

2.1. Lewin’s change model

One of the early ideas of how to organise change comes from afore mentioned Kurt Lewin. In 1947 he first published his three step model (Lewin, 1947, pp. 34-36) known as “Unfreezing – Moving – Freezing”. In short, these phases are:

-

UNFREEZING – Recognise the need for change and weaken the reluctance, prepare for the change-process

-

MOVING - Change or transition, effect organisational changes while “unstable”

-

FREEZING - Re-establish once change is completed.

2.2. Nadler & Tushman’s congruence model

In 1980 David Nadler and Michael Tushman (Nadler & Tushman, 1980) (Nadler, et

al., 1989) first published their model for diagnosing organisational behaviour. Their Congruence Model bases on the principle that an organisation's performance derives from four key

elements: people, tasks, the formal and the informal organisation (structure and culture).

Figure 4: A Congruence Model for Organization Analysis (Nadler & Tushman, 1980, p. 47)

The three steps to use their model are:

-

Separately analyse the key elements,

-

Analyse the elements’ interrelation within the organisation

-

Create and maintain congruence among the elements

Essential is the congruence between the four elements, higher congruence according to their model means greater performance. For example even the newest technology and perfectly streamlined processes supporting decision making will not fit into a highly bureaucratic organizational culture where even the most brilliant people could not shine through.

2.3. The Beckhard-Gleicher change formula

First published in 1975 by Richard Beckhard (1975, p. 45) with an attribution to David Gleicher who first had the idea in the early 1960’s the original formula was:

C = (ABD) > X

Whereas the variables stand for: C is change, A is the degree of dissatisfaction with the status quo, B is the clear desired state, D is practical steps towards the desired state and X is the cost of the change.

In 1992 it was Kathleen Dannemiller (Dannemiller & Jacobs, 1992) who made the formula more accessible by simplifying the variables and putting them in mnemonics. The result was:

D x V x F > R

Dannemiller changed the A for a D (dissatisfaction), the B for a V (vision), the D for an F (first steps) and the X for an R (resistance to change) while the product of the first three factors had to be greater than the resistance to change to make change possible. Is any of the factors missing or tending to zero means the product decreases and may not be greater than the resistance to change.

While in the time since the academic discussion went on it was Steven Cady (2014) who added an S for sustainability to the formula as he saw the need to ensure that gains made during a change process are sustainable. His formula then looked like this:

D x V x F x S > R

2.4. Kotter’s eight steps of change

It was John Kotter (1995) who in 1995 systematically explained eight steps how to ‘organise’ change.

Kotter emphasizes on establishing a sense of urgency, to continue with the motivational drivers and the creation and communication of the vision while empowering others to act on this vision. The

planning and creation of short-term wins and the formalization of new processes and procedures are accounted by him as motivational factors along the way to his final step of institutionalising

new approaches.

Figure 5: Kotter's eight steps of change (1995)

3. Conclusions

Leadership could be defined in short words as the process through which a leader

influences his followers to achieve shared objectives. James McGregor Burns formulated that

leaders with relevant motives and goals of their own respond to the followers’ needs and wants and goals in such a way as

to meet those motivations and bring changes consonant with those of both leaders and followers, and with the values of both (Burns, 1978, p. 41).

Peter Drucker once said about successful leaders:

Successful leaders don’t start out asking, “What do I want to do?” They ask, “What needs to be done?” Then they ask, “Of

those things that would make a difference, which are right for me?” They don’t tackle things they aren’t good at. They make sure other necessities get done, but not by them. Successful leaders

make sure that they succeed! They are not afraid of strength in others. (Drucker, 2004)

Finally, there is no one truth, no perfect, universal leadership style. As Daniel

Goleman (2000) said “The best leaders don’t know just one style of leadership – they are skilled at several, and have the flexibility to

switch between styles as the circumstances dictate.”

As with leadership styles there are several models, concepts and ideas in literature

about how to lead change. Finally it is all about successfully leading change and therefore there is again not the one and only truth.

Resistance to change appears to be a natural, human reaction; we all resist to leave

our comfort zone though being forced to we mostly recognize the need for. As said earlier Kotter’s 8 steps may seem obvious to many however much too often one of the steps is left out or

integrated too late or even too early.

In 2012 Kotter expanded on his eight step model and developed the ‘Eight

Accelerators’. Kotter (Kotter, 2012) explains that there are three main differences between the eight steps and the

accelerators:

-

The steps are often used in rigid, finite and sequential ways […] whereas the accelerators are concurrent and always at work.

-

The steps are usually driven by a small, powerful core group, whereas the accelerators pull in as many people as possible […] to form a voluntary army.

-

The steps are designed to function within a traditional hierarchy, whereas the accelerators require the flexibility and agility of a network.

Both Kotter’s models are relevant and effective today, but they are

designed to serve different contexts and objectives. Further discussion and expansion on Kotter’s amplified model must be left to someone else as this would go beyond the scope of this

paper.

There is no such thing as a universal recipe for any organisational

change, however, Kotter’s eight step concept comes quite close to one. Every organisational change is different, has a different environment, different reasons and affects different people.

Nonetheless Kotter’s steps three to six appear crucial as these are the steps that involve the people that finally have to be convinced, prepared and skilled to embrace the change. The situation

where the unwilling has to be led by the incompetent towards an uncertain future is to be avoided in any circumstances.

C. Michael Dell leading Change at DELL Inc.

Michael Dell stepped back from the position as CEO in 2004. In 2007, on Dell’s return as CEO, Paul D. Bell, senior vice president at DELL said: “It’s not all about Michael versus someone else before, Michael was here. He was chairman. But it was up to Michael to take the first-mover role in driving change and he did it” (Lohr, 2007). Just recently in 2013, shortly before the 30th birthday of DELL Inc., Michael Dell completed the largest corporate privatization in history when taking DELL Inc. private again. He commented: "You can't keep doing the same thing and expect it to keep working. We had to do something different." (Foster, 2014)

Since Dell is back he repeatedly emphasized that the Dell model “is not a religion” and he, who was once known as a short-term-thinker, a man by-the-numbers, seems now to be planning many years ahead. He changed his way by introducing a new leadership board, delegating power and sharing decision making. Since then Dell introduced a lot of changes. David Yoffie from Harvard Business School (Lohr, 2007) said: “This is going to be about changing the way they do business at many levels.” Dell stepped beyond his selling-direct-model and again forged retail agreements with WalMart, Carphone Warehouse and even Tesco. He started acquiring businesses, Alienware, ACS, EqualLogic, Perot Systems and just this month EMC, to name just few. With the acquisition of Zing Systems they finally stepped into the section of hand-held-devices. Though more than 80 percent of its sales is from corporate customers Dell accepted that they need to focus more on the consumer market to stay on top. In point of marketing they came up with a new slogan: “One Company, One Brand, One Beat” giving the brand a makeover. “Hey, we’ve got a lot of work to do and we’re just getting started”, Steve Lohr (2007) from the New York Times quotes Dell. And he got started.

DELL’s company core business was always server solutions. PC business being called dead from several sides, DELL focussed on getting into the mobile and tablet market. Given the strong presence of Apple’s iPad and Samsung’s Galaxy, that failed in 2011. DELL faced an enormous process of change in the past eight years shifting their strategy away from low-margin PCs towards higher-margin systems and services for corporate customers.

“At DELL, we never talk about ‘managing change’ or ‘dealing with change’ because change is all we‘ve ever known.[…] change promotes growth” said Michael Dell (1999, p. 214). However, he emphasized that planning for and communicating clearly opportunities is the way to encourage employees to embrace change without fear “There’s no risk in preserving the status-quo, but there’s no profit, either” (Dell, 1999, p. 222).

Michael Dell is not only open for change, he knows how to plan and communicate for it. “Dell went public because the company needed capital” (Dell, 2015). They now went private again because without dividends and buybacks, they now will have increased cash-flow and without the public markets to worry about, they have much more flexibility.

Analysing Dell’s leadership shows changes in his leading style. In his early life he was autocratic and it was him to make the decisions. He became participative when he started sharing management and reaching out to hire high-profile managers. He had a unique approach to leadership when he and Kevin Rollins led DELL together, both in the position as CEOs. When he introduced the leadership board in 2007 he showed again his willingness to share power and seek other people’s advice.

I’ve always tried to surround myself with the best talent I could find. When you’re the leader of a company, be it large or small, you can’t do everything yourself. The more talented people you have to help you, the better off you and the company will be. (Dell, 1999)

It occurs that the way Dell changed his style to fit the circumstances is

a situational leadership style. However, his influence on people more results from his characteristics than from his leadership style. Similarly to Steve Jobs in his early years, who was known to

be nervous, nerdy and almost appeared to be clumsy, they both grew with their responsibilities and both became not only charismatic persons but finally became great leader through their charisma.

All that points more to a transformational leadership style. It is his characteristics that resulted in people giving him credibility, trust and confidence. DELL staff developed a sense of

loyalty that goes beyond what an average leader gets back from his employees. Michael Dell does not only provide his people with inspiration and requires them to be inspirational, he too shows

ethical behaviour founding the ‘Michael & Susan Dell Foundation’ to improve the health and education of children worldwide. In 2014 and 2015 DELL was recognized as one of the World’s Most

Ethical Companies by the Ethisphere Institute (2015). The trusting and open climate he created by helping and

empowering others to be successful, by encouraging them to do more is the result of his idea of creating a “Company of Owners”.

Bibliography

Beckhard, R., 1975. Strategies for large system change. Sloan Management Review, 16(2), pp. 43-55.

Burnes, B., 2004. Kurt Lewin and the Planned Approach to Change: A Re-appraisal. Journal of Management Studies, 41(6), pp. 977-1002.

Burns, J. M., 1978. Leadership. 1st ed. New York(NY): Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc..

Cady, S. H., Jacobs, R. W., Koller, R. & Spalding, J., 2014. The Change Formula: Myth, Legend, or Lore?. OD Practioner, 46(3), pp. 32-39.

Dannemiller, K. D. & Jacobs, R. W., 1992. Changing the way organizations change: A revolution in common sense. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 28(4), pp. 480-498.

Dell, M., 1999. Direct from Dell - Strategies that revolutionized an industry. 1st ed. London: Harper Collins.

Dell, M., 2015. Michael Dell on Going Private, Company Management, and the Future of the Computer [Interview] (23 01 2015).

Drucker, P. F., 2004. Peter Drucker On Leadership [Interview] (26 10 2004).

Duck, J. D., 1993. Managing Change: The Art of Balancing. Harvard Business Review, November-December 1993, pp. 109-118.

Ethisphere Institute, 2015. World’s Most Ethical Companies – Honorees. [Online]

Available at: http://ethisphere.com/worlds-most-ethical/wme-honorees [Accessed 04 10 2015].

Foster, T., 2014. Michael Dell: How I Became an Entrepreneur Again. Inc. Magazine, July/August 2014.

Goleman, D., 1998. What Makes a Leader?. Harvard Business Review, November-December 1998, pp. 92-102.

Goleman, D., 2000. Emotional intelligence: Leadership That Gets Results. Harvard Business Review, March-April 2000, pp. 78-90.

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R. & McKee, A., 2001. Primal Leadership: The Hidden Driver of Great Performance. Harvard Business Review, December 2001, pp. 42-51.

Kirkpatrick, S. A. & Locke, E. A., 1991. Leadership: do traits matter?. Academy of Management Executive, 5(2), pp. 48-60.

Kotter, J. P., 1995. Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail. Harvard Business Review, March-April 1995, pp. 59-67.

Kotter, J. P., 1996. Leading Change. 1st ed. Boston(MA): Harvard Business School Press.

Kotter, J. P., 2012. Accelerate!. Harvard Business Review, November 2012, pp. 44-58.

Lewin, K., 1947. Frontiers in Group Dynamics. Human Relations, 1(1), pp. 5-41.

Lewin, K., Lippitt, R. & White, R., 1939. Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created social climates. Journal of Social Psychology, 10(2), pp. 271-301.

Lohr, S., 2007. Can Michael Dell Refocus His Namesake?. [Online]

Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/09/technology/09dell.html?pagewanted=print&_r=0 [Accessed 14 10 2015].

McGregor, D., 1960. The Human Side of Enterprise. 1st ed. New York(NY): McGraw-Hill.

Nadler, D. A. & Tushman, M. L., 1980. A Model for Diagnosing Organizational Behavior. Organizational Dynamics, 9(2), pp. 35-51.

Nadler, D. A., Tushman, M. L. & O'Reilly, C. A., 1989. The management of organizations: strategies, tactics, analyses. 1st ed. New York(NY): Ballinger Pub. Co..

Stogdill, R. M., 1948. Personal Factors Associated with Leadership: A Survey of the Literature. Journal of Psychology, 25(1), pp. 35-71.

Team FME, 2015. Leadership Theories - Leadership Skills. [Online]

Available at: http://www.free-management-ebooks.com/dldebk-pdf/fme-team-leadership.pdf

[Accessed 23 09 2015].